Washington Post, May 12, 2011: Senior US Officials Call on Secretary Clinton to Delist MEK

Iranian dissidents and a U.S. dilemma

REUTERS NEWS AGENCY

WASHINGTON — Call it the coalition of the baffled — a diverse group of prominent public figures who challenge the U.S. government’s logic of keeping on its terrorist blacklist an Iranian exile organization that publicly renounced violence a decade ago and has fed details on Iran’s nuclear programme to American intelligence.

On the U.S. Department of State’s list of 47 foreign terrorist organizations, the Mujahedin-e-Khalq is the only group that has been taken off similar lists by the European Union and Britain, after court decisions that found no evidence of terrorist activity in recent years. In the U.S., a court last July ordered the State Department to review the designation. Nine months later, that review is still in progress and supporters of the MEK wonder why it is taking so long.

The organization has been on the list since 1997, placed there by the Clinton administration at a time it hoped to open a dialogue with Iran, whose leaders hate the MEK for having sided with Saddam Hussein in the Iraq-Iran war.

Calls to hasten the delisting process rose in volume after Iraqi troops raided the base of the MEK northeast of Baghdad, near the Iranian border, in an operation on April 8 that left at least 34 dead, according to the United Nations Human Rights chief, Navi Pillay. In Washington, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, John Kerry, called the raid a “massacre.” Video uploaded by the MEK showed gut-wrenchingly graphic images of dead and wounded, some after being run over by armoured personnel carriers.

The raid drew cheers from officials in Iran, where the group is also classified as terrorist, one of the few things on which Washington and Tehran agree. The word schizophrenia comes to mind here. Iran is one of four countries the U.S. has declared state sponsors of terrorism. The MEK’s stated aim is the peaceful ouster of the Iranian theocracy. Isn’t there something wrong with this picture?

In response to the April 8 violence, MEK supporters organized a seminar in Washington whose panelists highlighted the bipartisan nature of those critical of the terrorist label. It’s not often that you see the former chairman of the Democratic National Committe, Howard Dean, a liberals’ liberal, sitting next to Rudolf Giuliani, the arch-conservative former mayor of New York.

At a similar event in Paris on the same day, the podium was shared by Nobel peace prize winner Elie Wiesel, Gen. James Jones, U.S. President Barack Obama’s former national security adviser, former NATO commander Wesley Clark and MEK leader Maryam Rajavi. The theme at both events – take the MEK off the list and protect the around 3,400 Iranians in Iraq, who live in Ashraf, a small town surrounded by barriers and security fences.

To hear Dean tell it in Washington, the April 8 raid was evidence that the Iraqi government is becoming “a satellite government for Iran,” with the terrorist designation used to justify “mass murder.” Dean is not alone in ascribing this and a previous attack that killed 11 in Ashraf in July 2009 to the growing influence of Iran as the U.S. prepares to withdraw most of its troops from Iraq by the end of the year.

WHAT NEXT?

What then? You don’t have to be a pessimist to anticipate more raids, more bloodshed and a humanitarian crisis. Until the end of 2008, the U.S. was responsible for the security of Ashraf and its residents enjoyed the status of “protected persons” under the Geneva Convention. That changed when the U.S. transferred control of Ashraf to the Iraqi government which provided written assurances of humane treatment of its residents.

They don’t seem to be worth the paper they are written on. The Iraqi raid on April 8 came a day after U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates was in Baghdad for talks with Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. One of the topics Gates raised — Iran’s influence in the region.

That Ashraf and the terrorist label for its inhabitants would put the United States in an awkward position after the transfer of responsibility was spelt out with remarkable clarity in February 2009 in a cable from the U.S. embassy in Baghdad. Marked secret and released through Wikileaks, the cable said harsh Iraqi action would place the U.S. in “a challenging dilemma.”

“We either protect members of a Foreign Terrorist Organization against actions of the ISF (Iraqi Security Forces) and risk violating the U.S.-Iraqi Security Agreement or we decline to protect the MEK in the face of a humanitarian crisis, thus leading to international condemnation of both the USG (U.S. government) and the GOI (government of Iraq).”

Which raises a question. How could the U.S. fail to protect unarmed Iranian dissidents opposed to a dictatorship but go to war to protect Libyans in a conflict between armed rebels and a dictatorship? Unlike the Libyan rebels, of whom little is known, the Iranians in Ashraf were all subject to background checks by the American military in the six years it was in control of the camp.

If there’s logic in protecting one but not the other, it’s not easy to see.

http://blogs.reuters.com/bernddebusmann/2011/04/29/iranian-dissidents-and-a-u-s-dilemma/

No Good Options for Iranian Dissidents in Iraq

By Patrick Clawson

April 19, 2011

In an April 8 confrontation at Camp Ashraf, Iraq — home to some 3,400 members of the Iranian dissident organization Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK) — Iraqi army forces killed at least thirty-four people, according to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay. The clash highlighted an ongoing problem: what to do about the presence of several thousand people the Iraqi government badly wants to be rid of, when no other country to which they are willing to go will accept them. Distasteful as the current situation is, the status quo may be best.

The Confrontation

When Iraqi forces entered Camp Ashraf on April 8, Baghdad initially claimed that no shots had been fired. The government later changed its story, however, stating that three people had been killed in clashes between rock-throwing residents and security forces had simply been redeploying. On the day of the attack, the U.S. State Department announced, “Although we do not know what exactly transpired early this morning at Ashraf, this crisis and the loss of life was initiated by the Government of Iraq and the Iraqi military.

Under pressure, Baghdad allowed a UN team into Ashraf after a five-day delay. According to Pillay, “It now seems certain that at least 34 people were killed…including seven or more women…Most were shot, and some appear to have been crushed to death, presumably by vehicles…There is no possible excuse for this number of casualties.” Pillay’s account was consistent with footage released by the MEK showing columns of Iraqi armored personnel carriers entering the camp; vehicles are seen running down residents, and riflemen are seen shooting from close range, including at women. Camp witnesses have stated that 2,500 soldiers from eight battalions of Iraq’s Ninth and Fifth Divisions participated in the attack.

As Iraqi forces remain in position to launch further military action, a recent statement by an Iranian official called for additional assaults. According to a report by the Fars News Agency — often regarded as being close to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps — Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s advisor for military affairs, Maj. Gen. Yahya Rahim Safavi, “praised the Iraqi army for its recent attack on the strongholds of the anti-Iran terrorist [MEK] and asked Baghdad to continue attacking the terrorist base until its destruction.”

MEK Background

Designated by the State Department as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, the MEK was an underground opposition group in the shah’s Iran during the 1960s and 1970s. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the group fell out with the new regime, which imprisoned, tortured, and killed thousands of its members. The remnants fled to Iraqi sanctuaries, where they formed an armed force against Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War. There also is evidence that Saddam Hussein used the MEK against his domestic opponents, though the group denies this.

Today, Tehran loathes the MEK and continues to arrest, imprison, and execute accused members. The regime tends to blame the group for a great deal of Iranian dissident activity, including in cases where there is little evidence of any such link. In fact, the group disarmed following Saddam’s overthrow in 2003, and no credible evidence exists showing MEK military action since then. The MEK formally renounced violence in 2004, which provided the basis for U.S. acknowledgement of a ‘protected persons’ status. Initially protected by U.S. forces, Camp Ashraf has been under Iraqi control since 2009.

Alternatives

Washington has repeatedly stated its interest in resolving the Ashraf situation. As State Department spokesman Mark Toner put it on April 12, “We’re prepared to consider any assistance that we can — that is requested by the Government of Iraq to develop and execute a negotiated plan to address the future of Camp Ashraf.” Preparing such a plan will not be easy, however, because each available option is deeply flawed.

Repatriation to Iran. Camp residents have announced that their first choice would be to go to Iran, but only if the Islamic Republic agreed not to jail or persecute them for their past opposition efforts. Yet securing a guarantee that satisfied the residents would probably be difficult. And forcing MEK members to return to Iran against their will would violate several international agreements to which Iraq is party.

In 2007, UNHCR cautioned Baghdad to refrain from any action that could endanger the lives or security of camp residents, such as deportation to another country or forced displacement inside Iraq. Similarly, the International Committee of the Red Cross reminded Baghdad of its obligation to act in accordance with the principle of nonrefoulement — that is, refugees should not be dispersed to a place where they would fear persecution. Washington reiterated these concerns on April 12, noting how Iraqi authorities “have provided written assurances that Camp Ashraf residents would be treated humanely” and that none of them would be “forcibly transferred to any other country where they might face persecution.”

Settlement in a third country. If safe return to Iran proves impossible, camp leaders have stated that their second preference is to go to a European Union member country or the United States. But none of these countries is willing to take them. The State Department’s continued designation of the MEK as a terrorist entity makes resettling group members in the United States impossible. It also considerably weakens Washington’s leverage in urging other countries to accept them instead. The issue of whether the MEK actually belongs on the terrorism list was discussed in PolicyWatches 1366 and 1643. Here, it is appropriate to point out that the designation poses an important complication in resolving the diplomatic quandary over Ashraf.

A puzzling development is that UNCHR spokesman Andrej Mahecic recently said that agency is ready to accept applications for refugee status from camp residents if they sign individual statements renouncing violence as a means of achieving their goals. Although he contends that Ashraf residents have been unwilling to do so, the MEK disputes this.

Formal status in Iraq. If resettling in the West proves untenable as well, camp leaders have stated that they wish to remain in Iraq near the Iranian border in order to promote nonviolent resistance and keep hope alive for a return to Iran when the regime collapses. Yet formally accepting the presence of Ashraf residents is politically unacceptable to some of the largest parties in the Iraqi governing coalition, including those closest to Iran. Tehran has made the MEK presence a major issue in bilateral relations, and harassing the group is one way for Baghdad to cultivate better ties with the Islamic Republic.

The MEK and its allies have long held unrealistic expectations about what Washington might do on behalf of Ashraf residents, such as opposing the 2009 handover of security responsibility for the camp perimeter to the Iraqi government. U.S. supporters of the group argue that continued protection of the MEK presence in Ashraf should be an American objective in negotiations regarding post-2011 cooperation with Baghdad. Yet Washington is unlikely to take on a cause so controversial in Iraqi politics on behalf of a group the State Department insists is a terrorist organization.

Status Quo Better than Alternatives

Barring the emergence of another alternative, the most feasible way forward is for the MEK members to remain in Ashraf, provided there are no further attacks against the residents. When acting Iranian foreign minister Ali Akbar Salehi visited Baghdad in January, Iraqi foreign minister Hoshyar Zebari announced that Baghdad was “determined to deal with this [MEK] issue,” adding, “There are some humanitarian commitments to which our government is loyal, but fulfilling these undertakings should not harm Iraq’s national sovereignty.” That is a good formulation; now it is up to Washington to work with Baghdad to ensure that practice on the ground meets that standard. Toward that end, the United States should urge the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) to enhance its involvement. For example, the MEK and its friends in the U.S. Congress allege — and Baghdad denies — that the camp residents have been subject to harassment, psychological pressure from hundreds of loudspeakers, and medical restrictions. UNAMI or a similar agency could prove helpful as a neutral third-party arbiter able to report on the situation firsthand.

Patrick Clawson is director of research at The Washington Institute.

Obama, Iran and a push for policy change

REUTERS NEWS AGENCY

Could the administration of President Barack Obama hasten the downfall of Iran’s government by taking an opposition group off the U.S. list of terrorist organizations? To hear a growing roster of influential former government officials tell it, the answer is yes.

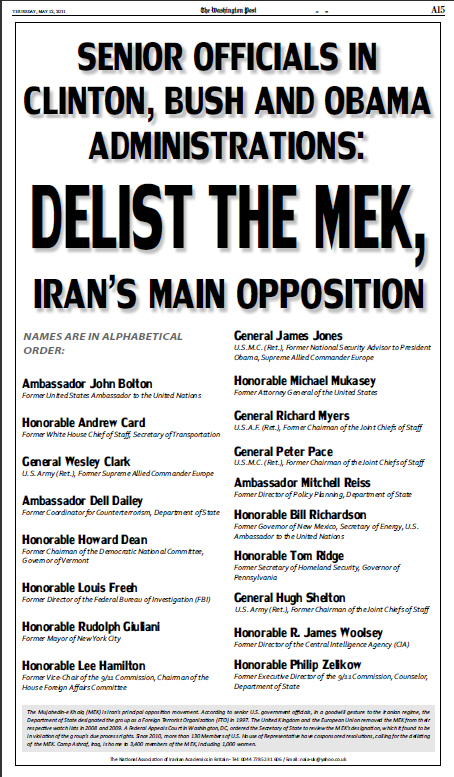

The opposition group in question is the Mujadeen-e-Khalq (MEK) and the growing list of Washington insiders coming out in its support include two former Central Intelligence Agency chiefs (James Woolsey and Michael Hayden), two chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Peter Pace and Hugh Shelton), former Attorney General Michael Mukasey, former Homeland Security chief Tom Ridge and former FBI head Louis Freeh.

The MEK was placed on the terrorist list in 1997, a move the Clinton administration hoped would help open a dialogue with Iran, and since then has been waging a protracted legal battle to have the designation removed. Britain and the European Union took the group off their terrorist lists in 2008 and 2009 respectively after court rulings that found no evidence of terrorist actions after the MEK renounced violence in 2001.

In Washington, initial support for “de-listing” came largely from the ranks of conservatives and neo-conservatives but it has been spreading across the aisle and the addition of a newcomer of impeccable standing with the Obama administration could herald a policy change not only on the MEK but also on dealing with Tehran.

The newcomer is Lee Hamilton, an informal senior advisor to President Obama, who served as a Democratic congressman for 34 years and was co-chairman of the commission that investigated the events leading to the September 11, 2001 attacks on Washington and New York.

“This is a big deal,” Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett, two prominent experts on Iran, wrote on their blog. “We believe that Hamilton’s involvement increases the chances that the Obama administration will eventually start supporting the MEK as the cutting edge for a new U.S. regime change strategy towards Iran.” The Leveretts think such a strategy would be counter-productive.

But speakers at the February 19 conference in Washington where Hamilton made his debut as an MEK supporter thought otherwise. Addressing some 400 Iranian-Americans in a Washington hotel, retired General Peter Pace said: “Some folks said to me if the United States government took the MEK off the terrorist list it would be a signal to the Iranian regime that we changed from a desire to see changes in regime behavior to a desire to see changes in regime. Sounds good to me.”

The Obama administration’s policy is not regime change but the use of sanctions and multi-national negotiations to persuade the government in Tehran to drop its nuclear ambitions. So far, that has been unsuccessful. Two rounds of talks between Iran, the U.S., China, Russia, France, Britain and Germany in January ended without progress and did not even yield agreement on a date for more talks.

NO POLICY CHANGE BUT SHARPER RHETORIC

That did not change Washington’s “no regime change” stand. What has changed is the tone of public American statements on Iran since a wave of mass protests swept away the authoritarian rulers of Tunisia and Egypt and forced the governments of Jordan, Bahrain, Yemen, Algeria and Saudi Arabia to announce reforms. In contrast, Iran responded to mass demonstrations with violent crackdowns.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared that the U.S. “very clearly and directly support the aspirations of the people who are in the streets” of Iranian cities agitating for a democratic opening as they did in 2009, when Washington stayed silent.

Like the U.S., Iran labels the MEK a terrorist organization and has dealt particularly harshly with Iranians suspected of membership or sympathies. In the view of many of its American supporters, the U.S. terrorist label has weakened internal support for the MEK. How much support there is for the organization is a matter of dispute among Iran watchers, many of whom consider it insignificant.

At last week’s Washington conference, however, speaker after speaker described it as a major force, feared and hated by the Iranian government. General Shelton called it “the best organized resistance group.” Dell Daley, the State Department’s counter-terrorism chief until he retired in 2009, said the MEK was “the best instrument of power to get inside the Iran mullahs and unseat them.”

The decision to give legitimacy, or not, to the group is up to Hillary Clinton. Last July, a federal appeals court in Washington instructed the Department of State to review the terrorist designation, in language that suggested that it should be revoked. Court procedures gave her until June to decide.

MEK Is Not a Terrorist Group

The National Review Online

The material-support statute is fine; the designation is the problem.

The moral of this story may be that sometimes it’s better not to have friends, especially the sort with easy access to the op-ed page of the New York Times, or “The Newspaper of Record,” as it sometimes bills itself.

About a week ago, in the guise of defending us against an imagined prosecution for materially assisting a foreign terrorist organization based on our comments at a conference where we urged that Mujahadin e Khalq (“MEK”) be removed from the State Department’s list of such organizations, Prof. David Cole of Georgetown Law School took to the op-ed page of the Times with a bit of rhetorical jujitsu designed to enlist us in his campaign to change the federal statute that bars such assistance. The liberal blogosphere salivated at the suggestion that four conservative Republicans were providing material support to a terrorist organization, notwithstanding Professor Cole’s tongue-in-cheek defense.

MEK, which opposes the current regime in Tehran and has provided valuable intelligence to the United States on Iranian nuclear plans, was placed on the State Department list during the Clinton administration as a purported goodwill gesture to the mullahs, in aid of furthering dialogue. Regrettably, it was kept on during the administration of George W. Bush, in part out of fear that Iran would provide IEDs to our enemies in Iraq, which of course the mullahs are doing anyway. Both the European Union and the United Kingdom have removed the organization from their lists, with the result that MEK is now designated a terrorist organization by only the United States and Iran. More than 100 members of Congress have supported a resolution to undo this designation. We appeared at a conference two weeks ago and described why we thought the designation was anomalous and unwarranted.

Professor Cole’s arch suggestion that our conduct raises a question under the material-support statute is undone by the text of the law itself. The statute barring material assistance to organizations on the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations (“FTO”) says that although “material assistance” includes “personnel,” and although “personnel” may include the person providing the assistance — here, the four of us — the “personnel” have to be working “under that [FTO’s] direction or control.” And then, just to make explicit what is already obvious, the law continues: “Individuals who act entirely independently of the [FTO] to advance its goals or objectives shall not be considered to be working under the [FTO]’s direction and control.” As a result, we felt quite secure, thank you, in relying on the protection Congress placed in the statute, backed up by the First Amendment.

Professor Cole commendably if somewhat unnecessarily insisted in his article that we “had every right to say what [we] did,” but then added — misleadingly — that he “argued just that in the Supreme Court, on behalf of the Los Angeles–based Humanitarian Law Project” in the case he lost in that tribunal last June. Well, no. He argued that the statute should be rewritten to provide that the two activities the self-styled humanitarians wanted to engage in — “training” in negotiation, and “expert advice and assistance” in filing claims, both quoted activities specifically barred by the law — should be permitted unless they involved directly a terrorist act. The Court refused to do that, or to find that the quoted terms were either so vague as not to provide notice to a person of reasonable intelligence or gave the government unlimited latitude in applying the law. Further, the Court found that insofar as these terms could be imagined to reach activities shielded by the First Amendment, they were not activities these humanitarians were seeking to engage in and therefore need not be considered by the Court. That is, Professor Cole and his client lost.

He then went a bit beyond us, and beyond his unsuccessful lawsuit, and called for revising the statute also to permit provision of food and shelter via terrorist organizations, apparently based on the disclosure in the Times that corporations have been permitted by our government to sell — at profit, no less — chewing gum, popcorn, and cigarettes to state sponsors of terrorism. The reasoning here is apparently that if it’s okay to sell chewing gum to terrorists, it’s okay to give them concrete they can use not only for shelter but also to fashion bunkers, or to give them the spigot controlling the flow of food and medicine so they can enhance their power and prestige. For what it’s worth, we do not believe that Professor Cole has unearthed an insufferable anomaly in the law or in its administration. Notably, neither in his lawsuit nor in his op-ed did Professor Cole challenge the designation FTO as applied to the proposed beneficiaries of his client’s ministrations. We have challenged, emphatically and with reasoned argument, that designation as applied to MEK.

The material-support statute doesn’t need revision to accommodate non-existent defects. What it does need — and does not often enough get for fear of offending some Muslim organizations — is rigorous enforcement against accurately designated organizations, of which MEK is not one.

Why, you may ask, did this critique not appear in the pages of The Newspaper of Record (TNOR)? Good question. The editors of TNOR deemed a much shorter version of this article too long for their letters column, and declined to publish it as an op-ed article because, they claim, TNOR has a policy of not publishing op-ed articles in response to other op-ed articles. We are grateful to the editors of National Review for the privilege of this space, and of course to Professor Cole for his unsolicited support, even though we decline to enlist in his crusade.

— Michael B. Mukasey was attorney general of the United States from 2007 to 2009; Tom Ridge was homeland security adviser to Pres. George W. Bush from 2001 to 2003, and homeland security secretary from 2003 to 2005; Rudolph W. Giuliani was mayor of New York City from 1993 to 2001; Frances Fragos Townsend was homeland security adviser to Pres. George W. Bush from 2004 to 2008.

Washington Times, December 1, 2010: US Lawmakers Call on Secretary Clinton to Delist MEK

America, Iran and a terrorist label

REUTERS NEWS AGENCY

Who says that the United States and Iran can’t agree on anything? The Great Satan, as Iran’s theocratic rulers call the United States, and the Islamic Republic see eye-to-eye on at least one thing, that the Iranian opposition group Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) are terrorists.

America and Iran arrived at the terrorist designation for the MEK at different times and from different angles but the convergence is bizarre, even by the complicated standards of Middle Eastern politics. The United States designated the MEK a Foreign Terrorist Organization in 1997, when the Clinton administration hoped the move would help open a dialogue with Iran. Thirteen years later, there is still no dialogue.

But the group is still on the list, despite years of legal wrangling over the designation through the U.S. legal system. Britain and the European Union took the group off their terrorist lists in 2008 and 2009 respectively after court rulings that found no evidence of terrorist actions after the MEK renounced violence in 2001.

On July 16, a federal appeals court in Washington instructed the Department of State to review the terrorist designation, in language that suggested that it should be revoked. But Hillary Clinton’s review mills appear to be grinding very slowly.

A group of lawmakers from both parties reminded Clinton of the court ruling this week and drew attention to a House resolution in June — it has more than 100 co-sponsors and the list is growing — that called for the MEK to be taken off the terrorist list. Doing so would not only be the right thing, the six leading sponsors said in a letter, it would also send the right message to Tehran. Translation: using the terrorist label as a carrot does not work, so it’s time to be tough.

Come January, when a new, Republican-dominated House of Representatives begins its term, Clinton and President Barack Obama are likely to come under pressure from hawkish members of congress to act tough towards Iran, further tighten economic sanctions and ensure that those already existing don’t erode.

The influential House Foreign Affairs Committee will be headed by Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, an enthusiastic MEK-backer, who said in a recent interview with Reuters correspondent Pascal Fletcher that the West must make clear it means business about implementing sanctions against Iran. “If…we convey a sense of weakness and a lack of resolve, the centrifuges (in Iran’s uranium enrichment program) keep spinning.”

GROUP BLEW WHISTLE ON NUCLEAR PROGRAM

Ironically, it was the MEK which gave the first detailed public account of Iran’s until-then secret nuclear projects at the cities of Natanz and Arak, in 2002. The disclosure greatly turned up the volume of the international controversy over Iran’s intentions. (Iran’s leaders firmly deny that work on nuclear bombs is underway).

Iran’s nuclear program is likely to rise close to the top of Obama’s foreign policy agenda in the second half of his mandate, particularly if there are no signs of progress in the on-again, off-again attempts to break the present stalemate. The next talks are scheduled for Dec. 5, between the so-called P5+1 (U.N. Security Council members Britain, France, Russia, China and the United States, plus Germany) and Iran.

Other than getting the United States in sync with its Western allies on their assessment of the MEK, what would taking it off the 47-strong American list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations change? In the United States, it would unfreeze frozen funds and allow the group to reopen its office and operate freely as an advocacy group.

In Iran, it would deprive the government of an all-purpose scapegoat to taint all reformists with the MEK brush. In arresting alleged members or sympathizers, Iranian authorities routinely mention that even the United States considers the group terrorist. In their letter to Clinton, the legislators argued that the U.S. designation allowed Iranian officials to “further justify their draconian punishments”.

How much support the MEK, whose leadership is based in Paris, enjoys in Iran is a matter of dispute and many experts rate it as insignificant. But there is no dispute over draconian punishments for Iranians judged to be members or sympathizers. That prompts charges of “waging war against God”, which is punishable by death.

The MEK’s appeal to the Washington court in summer was its fifth petition. It remains to be seen how long the United States. and Iran will stay on the same page on the matter.

What is the Purpose of the U.S. Foreign Terrorist Organizations List?

PolicyWatch #1643

By Patrick Clawson

March 18, 2010

The United States maintains a range of “terrorist lists,” of which the Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO) list is one of the better known. But in two recent court cases, the U.S. government has offered arguments that raise questions about the purpose of the list.

FTO List vs. State Sponsors List

Another list is that of state sponsors of terrorism. The act of naming a foreign government as a terrorism sponsor is one instrument among many to affect the general foreign policy stance of the country concerned. Yet in practice, the state sponsors category has become a list of governments Washington simply does not like, often with little connection to terrorism; witness the continued presence of Cuba and the longtime presence North Korea. By contrast, governments that actually do sponsor terrorism but that Washington does not wish to single out are omitted from the list. A case in point is Lebanon, whose governing coalition includes Hizballah, the terrorist activities of which are protected and defended by the Lebanese government.

The decision to attempt to affect a state’s foreign policy differs substantially from that of prohibiting material support to an organization, the latter being the objective specified in the law mandating the FTO list. Whereas the decision to influence a state’s foreign policy is political in intent, blocking support to terrorist groups is much more like a policing matter, on which the United States can hope for cooperation from foreign governments irrespective of their views about U.S. foreign policy. If decisions about listing organizations as sponsors of terrorism are made based on general foreign policy considerations rather than on evidence about terrorist activities, the list may well be seen as a political tool, in which case other governments will be less likely to cooperate in blocking material support to listed groups.

The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 stipulates that even if an organization is engaged in terrorism or retains the capability and intent to do so, national security considerations may warrant its removal from the FTO list. The law, however, does not provide for the reverse — that is, maintaining a listing for nonterrorist national security reasons. Instead, the law requires that a group be maintained on the list only if it “engages in terrorist activity.” When in 1999 the State Department dropped three groups from the FTO list, officials seemed to endorse the position that to remain on the list after the biennial review, a group had to have been involved in terrorist activities during the preceding two years.

The PKK Case

In February 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, in which the latter entity wanted to provide legal advice to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The PKK has changed names several times, with the most recent being Kongra Gele Kurdistane (Kurdistan People’s Congress). Further, it is worth noting that the PKK has a history of claiming to abandon terrorism but not doing so. Six months after Turkey captured PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan in February 1999, the organization declared a ceasefire and said it would disband in February 2002. But the PKK moved its terrorists from Turkey to northern Iraq and, within a few years, resumed its terrorist activities. This scenario illustrates the risk of taking at face value a group’s claim that it has abandoned terrorism.

Much of the argument against the Humanitarian Law Project in the Supreme Court case turned on the scope of the term “material support.” But an additional issue involved the character of the support provided, including advice on why and how to stop terrorist activities. Solicitor General Elena Kagan, who represented the U.S. government, asked, “Can you say to an organization, look, you guys really should lay down your arms?… Well, now you can’t. Because when you tell people, here’s how to apply for aid and here’s how to represent yourself within international organizations or within the U.S. Congress, you’ve given them an extremely valuable skill that they can use for all kinds of purposes, legal or illegal.” In this statement, Kagan suggests that it is illegal to advise groups to abandon terrorism. And yet one struggles to see how such a position advances the objective of countering terrorism. The State Department’s website states, “FTO designations…are an effective means of curtailing support for terrorist activities and pressuring groups to get out of the terrorism business.” Surely it is appropriate to encourage groups to drop their terrorist activities, as the United States successfully did with some extremist Irish Republican groups and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The People’s Mujahedin of Iran Case

The People’s Mujahedin of Iran (PMOI), aka Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), has been on the FTO list since the list was started in 1997. More than thirty years ago, a faction arising from PMOI engaged in terrorism against Americans. Yet if the criterion for being on the FTO list is whether a group has ever engaged in terrorism, then many organizations with which the U.S. government has important dealings, such as the PLO, belong on the list. Every two years after 1997, the FTO listing of PMOI was reviewed and retained, until 2004, when the time period for mandatory review was increased to five years. The decision by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2009 to maintain the FTO listing of PMOI did not set forth detailed reasons or criteria, other than stating that “the circumstances that were the basis for the 2003 redesignation…have not changed in such a manner as to warrant revocation.”

In repeated yet unsuccessful bids, PMOI has sought to have its designation overturned by U.S. courts, in cases decided in 1999, 2001, 2003, and 2004. By contrast, the group has had greater success in more recent attempts in Europe. Listings of PMOI as a terrorist organization by the European Union (EU) were in 2006-2008 repeatedly overturned by the European Court of Justice, and the EU Council of Ministers removed PMOI definitively from its terrorist list in January 2009. Two years prior, Britain’s Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission (POAC), which exists solely to review terrorist designations and has access to all classified British government information, ruled, “Having carefully considered all the material before us, we have concluded that the decision [made] at the First Stage [that PMOI was engaged in terrorism] is properly characterised as perverse. We recognise that a finding of perversity is uncommon.” In 2008, the English Court of Appeal stated, “The reality is that neither in the open material nor in the closed material was there any reliable evidence that supported a conclusion that PMOI retained an intention to resort to terrorist activities in the future.”

In January 2010, oral arguments were completed in the U.S. Court of Appeals-D.C. Circuit in the case of PMOI v. U.S. Department of Stateregarding the 2009 listing of the group. During the hearing, the government’s counsel acknowledged that the public portion of the administrative record was devoid of any evidence to justify the secretary of state’s decision. In other words, no unclassified statement had been released that summarized, or even hinted at, the classified evidence used by Secretary Rice in reaching her decision.

The 2009 decision to continue listing PMOI was striking on several grounds. First, according to the New York Times, the State Department’s top counterterrorism official, Ambassador Dell Dailey, pushed to have PMOI delisted, but Secretary Rice overruled Dailey and other counterterrorism professionals. Second, the secretary’s decision came after the European court cases won by PMOI, in which the group prevailed against repeated efforts by European governments to continue listing it — listings widely perceived to be for foreign policy purposes rather than based on counterterrorism principles. Third, the State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism contain numerous nonterrorist allegations against PMOI without offering any indication that the group continues to engage in terrorism. The most recent episodes cited are several years old, and those incidents arguably fit the Geneva Conventions’ criteria for irregular warfare rather than terrorism.

In light of these factors, and given that the original designation was described by the official then serving as assistant secretary of state for Near East affairs as an action taken after the Iranian government raised the matter, one can only wonder if the secretary’s decision was based on foreign policy considerations outside the criteria set out in the law.

It would seem to be in the U.S. interest to encourage PMOI to disengage from all terrorist activities. Perhaps the U.S. government does not accept the group’s oft-repeated claim to have abandoned terrorism. If so, Washington should inform PMOI of steps it must take to establish its bona fides. Failure to do so will only feed the perception that the continued FTO listing of PMOI is for reasons other than terrorism.

Patrick Clawson is deputy director for research at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

America, terrorists and Nelson Mandela

REUTERS NEWS AGENCY

Woe betide the organization or individual who lands on America’s terrorist list. The consequences are dire and it’s easier to get on the list than off it even if you turn to peaceful politics. Just ask Nelson Mandela.

One of the great statesmen of our time, Mandela stayed on the American terrorist blacklist for 15 years after winning the Nobel Prize prior to becoming South Africa’s first post-Apartheid president. He was removed from the list after then president George W. Bush signed into law a bill that took the label “terrorist” off members of the African National Congress (ANC), the group that used sabotage, bombings and armed attacks against the white minority regime.

The ANC became South Africa’s governing party after the fall of apartheid but the U.S. restrictions imposed on ANC militants stayed in place. Why? Bureaucratic inertia is as good an explanation as any and a look at the current list of what is officially labelled Foreign Terrorist Organisations (FTOs) suggests that once a group earns the designation, it is difficult to shake.

The consequences of a U.S. terrorist designation include freezing an organisation’s funds, banning its members from travelling to the U.S. and imposing harsh penalties (up to 15 years in prison) on people who provide “material support or resources” to an FTO.

At present, there are 44 groups on the list, ranged in alphabetical order from the Palestinian Abu Nidal Organisation to the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia. The Abu Nidal group, according to the government’s own country reports on terrorism, “is largely considered inactive.” The Congressional Research Service, a bipartisan agency which provides research and analysis for Congress, has wondered why it is still on the list.

One can ask the same about the Colombian group, added to the list in 2001. The bulk of the paramilitary organisation demobilized years ago and the latest U.S. government report says its “organizational structure no longer exists.”

In between Abu Nidal and the Colombians are groups whose terrorist acts and future intentions are undisputed – al Qaeda, Islamic Jihad – as well as one which is waging a protracted legal battle to have its terrorist label taken off.

EUROPE, U.S. OUT OF SYNCH

That is the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK), an Iranian resistance group on which the United States is out of synch with Britain and the 27-member European Union. After years of legal wrangling, Britain took the MEK off its terrorist blacklist in 2008 and the EU followed suit last year. In the last week of the administration of George W. Bush, then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice denied the group’s petition that its terrorist label be taken off.

The MEK’s case came up again this week in a wood-panelled Washington courtroom where high-powered lawyers debated whether Rice had acted “reasonably” in doing so.

Yes, she had, the government’s lawyer, Douglas Letter, told the three-judge panel, given the MEK’s past history of violence. In his written brief, he scoffed at “claims that ‘the tiger has changed its stripes,’” a reference to the group’s contention that it had foresworn violent acts in 2001 in favor of peaceful change.

Rulings by foreign courts, the argument went, were not germane to the case in the U.S. Those decisions included one by Britain’s Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission (POAC), a body established to review disputes over terrorist designations. The POAC found it would be “perverse” to stick to that label and ordered the Home Office to remove the MEK from the terrorist blacklist.

When the Washington Court of Appeals will rule on the MEK’s latest (and fifth) petition is not clear but if the past is any guide, political rather than legal considerations will decide the fate of the group in the U.S. American administrations have been using the terrorist organizations list and a separate list of “state sponsors of terrorism” as political tools.

Washington added the MEK to the terrorist list in 1997, at a time when the Clinton administration hoped the move would facilitate opening a dialogue with Iran and its newly-elected President, Mohammad Khatami, who was seen as moderate open to better relations with the U.S. The MEK served as a bargaining chip but the hoped-for dialogue didn’t go anywhere.

Neither did President Barack Obama’s diplomatic overtures to the theocrats ruling Iran. There has been no apparent progress on negotiations on Tehran’s nuclear ambitions and the government has turned deaf ears to international criticism of increasingly savage repression of anti-government dissent. Obama was guarded in his initial reaction to the crackdown on popular protests that erupted after Iran’s elections in June.

But he finally spoke out against the government in December: “For months, the Iranian people have sought nothing more than to exercise their universal rights. Each time they have done so, they have been met with the iron fist of brutality, even on solemn occasions and holy days.”

Despite the tough language, he has obviously not given up hope for negotiations. “We … want to keep the door to dialogue open,” Obama’s Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, said in January. Which probably means that the MEK, hated by Iran’s rulers, will retain its role as a bargaining counter and stay on the terrorist list.

http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2010/01/15/america-terrorists-and-nelson-mandela/